Ways of Seeing the City

03.30.2022

These central readings influence how I am structuring my thinking.

This book explores how the French military used architecture to suppress anticolonial insurgency in early 20th-century Algeria. For example, the French designed rigid housing typologies built en masse to “domesticate” semi-urban Algerians. The typology imported French cultural values, such as preference for housing only the nuclear family rather than extended families and limiting physical space for the families themselves to build upon the existing structure if more space was needed.

A second important theme in this book is the exportation of these urban planning techniques to the United States during post-WW2 city building. The very tactics that the French were using to enforce modern colonization on indigenous Algerians were then translated to the American context to build suburbs. This translation was happening at a time when American cities were in massive flux. Due to increasing diversity in cities, White Americans started to flee to urban peripheries while discriminatory lending policies dessimated predominantly Black communities through disinvestment. Thus we can see how French planning tactics imported from a vastly different geographic and cultural context were used to advise the production of American suburbs. While the geographic and political context was different, the political context was rooted in similar desires for control, homogeneity, eurocentrism, surveillance and conformity.

This reading sparked my interest in how urban design techniques are transported across cultures and geographies, how modes of building can reproduce colonial power structures and cultural values. It illustrates how high-level political ideas and cultural stories are manifested in physical form.

![]()

The second reading that gave structure to my research was urban sociologist Richard Sennet’s “Building and Dwelling”. This sweeping summary of how cities are built argues against the “closed city” - segregated, rigid, unable to adapt to change, and controlled - and instead advocates for an open city. The open city is one in which conflict and complexity are constantly engaged and used as a city building tool, in which city planners allow for multiple uses to overaly.

Three primary ideas arise from this book. This first is a framework within which to problem solve. Sennet distinguishes between boolean problem solving - concerned with moving in a linear direction to prove a hypothesis - with basean problem solving - interested in the relationship between problem solving and problem finding. Basean thinking looks closely at wrong answers, complexity, and building up rather than simplifying. Where boolean problem solving operates in a closed system, a basean approach manipulates the problem solving process, opening up potential for other outcomes. Cities are made up of systems (transportation, budgeting, public works, cultural production) and the types of problem solving that act as the foundation for these systems thus get manifested in the physical city itself. So as I start to think about how to create “open cities”, I want to incorporate basean, open problem solving processes. The summation of urban systems dictates the character of the city.

Secondly, Sennet states that the central problem of closed cities is citizens’s inability and discomfort with managing complexity. He proposes five methods for opening up a city.

1. One way to “open” up a “closed” city, is to increasing it’s complexity rather than simplify it, which was a very common planning tactic of the 20th century. Increased complexity forces residents need to engage with difference in the everyday. For example, Sennet critiques the “closed” nature of French urban planner Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin due to it’s tight fit between form and function. Difficult to modify, it is at risk of technical obsolescence because isolated residents won’t be able to adapt the space to their changing needs. I see this obsolescence in the abandoned shopping malls in Chicago suburbs. Built with a very narrow purpose - giving retail space to high-rent national franchises - the built form now is unable to adapt to changing social conditions of online shopping, for example. I also see this in the rigid structure of redlining. Maintaining who can live where within what tiny squares on a plot of land acording to arbitrary deliniations of physical characteristics created closed social and physical systems.

2. Synchronous centers - an urban center should be comprised of many layers of various uses overlapping each other.

3. We should design for “incomplete form”, which is concerned with how to build halves and parts so that over time things can evolve. The photos below of a housing project in Quinta Monroy, Chile illustrate how architects built structures that allowed for residents to make adjustments as desired post-occupation.

4. Clear and modest placemaking to note where things are.

5. Porous membranes

These criteria provide a foundation for the criteria I used to choose spaces to study while here in Belo Horizonte. Following blog posts will explore these places in more depth.

![]()

![]()

3. “

Outro Jogo de Linguagem Como Proposta Teórico-Metodológica da Leitura do Lugar“ Denise Morado Nascimento, Daniel Medeiros de Freitas, Gabriel da Cruz Nascimento (2021)

This third article was writted by my advisors at the PRAXIS research group here in Brazil. PRAXIS is a research group housed within the School of Architecture at the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

In English, the title is “Another language game as a theoretical-methodological proposal for reading places,” and it is surely a dense text that has taken MANY reads on my end. I am using two central themes from theoretical framework for “reading place” as a launching point to give more site-specific structure to my research. This section is deep in the works and incomplete as I try to translate from Portuguese to English these complex ideas.

First, the authors use Canter’s (1977) three spheres of consciousness to define how humans understand a place: physical attributes, activities, and sense. I’m using these categories to collect data for the spaces I am studying in Belo Horizonte.

Secondly, the authors discuss the process of “dencrypting” language to build a more open city. According to

the “Encryption of Power Theory” by Sanín-Restrepo (2016), language is used as a colonial tool to maintain power.

The authors applied this theoretical foundation to an online tool (link) that is mapping resident experiences in place and subvert the conventional language games about “place” that dominate urban planning in Belo Horizonte.

In their own words, “The platform leverages itself as a way for each resident to read their place, far beyond the categories-concepts and indicators-indices built by others. Therefore, it constitutes a proposal for the decryption of the city through the insertion of another language game in the political arena. It is necessary to show that our proposal does not aim to portray the territory, but to demonstrate the complexity of urban dynamics, commonly encrypted.”

1. “Architecture of Counterrevolution” Samia Henni (2018)

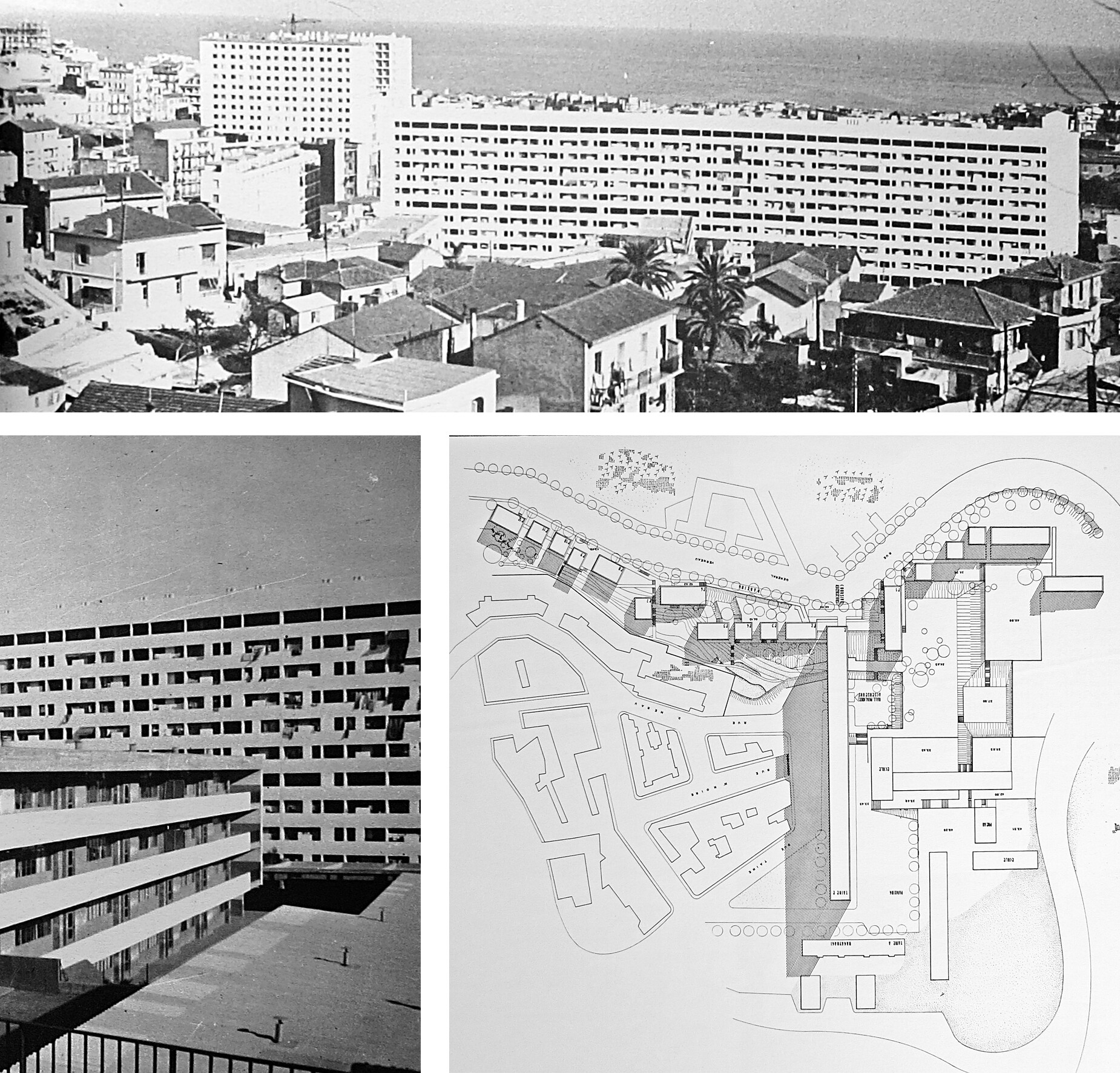

This book explores how the French military used architecture to suppress anticolonial insurgency in early 20th-century Algeria. For example, the French designed rigid housing typologies built en masse to “domesticate” semi-urban Algerians. The typology imported French cultural values, such as preference for housing only the nuclear family rather than extended families and limiting physical space for the families themselves to build upon the existing structure if more space was needed.

A second important theme in this book is the exportation of these urban planning techniques to the United States during post-WW2 city building. The very tactics that the French were using to enforce modern colonization on indigenous Algerians were then translated to the American context to build suburbs. This translation was happening at a time when American cities were in massive flux. Due to increasing diversity in cities, White Americans started to flee to urban peripheries while discriminatory lending policies dessimated predominantly Black communities through disinvestment. Thus we can see how French planning tactics imported from a vastly different geographic and cultural context were used to advise the production of American suburbs. While the geographic and political context was different, the political context was rooted in similar desires for control, homogeneity, eurocentrism, surveillance and conformity.

This reading sparked my interest in how urban design techniques are transported across cultures and geographies, how modes of building can reproduce colonial power structures and cultural values. It illustrates how high-level political ideas and cultural stories are manifested in physical form.

Housing settlements designed by French architects Alexis Daure and Henri Béri in Algiers, 1960s.

Source: Samia Henni. “From ‘Indigenous’ to ‘Muslim’”. E-Flux Architecture. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/positions/160964/from-indigenous-to-muslim/

Source: Samia Henni. “From ‘Indigenous’ to ‘Muslim’”. E-Flux Architecture. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/positions/160964/from-indigenous-to-muslim/

2. “Building and Dwelling” Richard Sennett (2018)

The second reading that gave structure to my research was urban sociologist Richard Sennet’s “Building and Dwelling”. This sweeping summary of how cities are built argues against the “closed city” - segregated, rigid, unable to adapt to change, and controlled - and instead advocates for an open city. The open city is one in which conflict and complexity are constantly engaged and used as a city building tool, in which city planners allow for multiple uses to overaly.

Three primary ideas arise from this book. This first is a framework within which to problem solve. Sennet distinguishes between boolean problem solving - concerned with moving in a linear direction to prove a hypothesis - with basean problem solving - interested in the relationship between problem solving and problem finding. Basean thinking looks closely at wrong answers, complexity, and building up rather than simplifying. Where boolean problem solving operates in a closed system, a basean approach manipulates the problem solving process, opening up potential for other outcomes. Cities are made up of systems (transportation, budgeting, public works, cultural production) and the types of problem solving that act as the foundation for these systems thus get manifested in the physical city itself. So as I start to think about how to create “open cities”, I want to incorporate basean, open problem solving processes. The summation of urban systems dictates the character of the city.

Secondly, Sennet states that the central problem of closed cities is citizens’s inability and discomfort with managing complexity. He proposes five methods for opening up a city.

1. One way to “open” up a “closed” city, is to increasing it’s complexity rather than simplify it, which was a very common planning tactic of the 20th century. Increased complexity forces residents need to engage with difference in the everyday. For example, Sennet critiques the “closed” nature of French urban planner Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin due to it’s tight fit between form and function. Difficult to modify, it is at risk of technical obsolescence because isolated residents won’t be able to adapt the space to their changing needs. I see this obsolescence in the abandoned shopping malls in Chicago suburbs. Built with a very narrow purpose - giving retail space to high-rent national franchises - the built form now is unable to adapt to changing social conditions of online shopping, for example. I also see this in the rigid structure of redlining. Maintaining who can live where within what tiny squares on a plot of land acording to arbitrary deliniations of physical characteristics created closed social and physical systems.

2. Synchronous centers - an urban center should be comprised of many layers of various uses overlapping each other.

3. We should design for “incomplete form”, which is concerned with how to build halves and parts so that over time things can evolve. The photos below of a housing project in Quinta Monroy, Chile illustrate how architects built structures that allowed for residents to make adjustments as desired post-occupation.

4. Clear and modest placemaking to note where things are.

5. Porous membranes

These criteria provide a foundation for the criteria I used to choose spaces to study while here in Belo Horizonte. Following blog posts will explore these places in more depth.

Housing units before resident occupation. Quinta Monroy, Chile.

Source: Elemental Arquitetos (2003)

Source: Elemental Arquitetos (2003)

Housing units after resident adjustments. Quinta Monroy, Chile.

Source: Elemental Arquitetos (2003)

Source: Elemental Arquitetos (2003)

3. “

Outro Jogo de Linguagem Como Proposta Teórico-Metodológica da Leitura do Lugar“ Denise Morado Nascimento, Daniel Medeiros de Freitas, Gabriel da Cruz Nascimento (2021)

This third article was writted by my advisors at the PRAXIS research group here in Brazil. PRAXIS is a research group housed within the School of Architecture at the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

In English, the title is “Another language game as a theoretical-methodological proposal for reading places,” and it is surely a dense text that has taken MANY reads on my end. I am using two central themes from theoretical framework for “reading place” as a launching point to give more site-specific structure to my research. This section is deep in the works and incomplete as I try to translate from Portuguese to English these complex ideas.

First, the authors use Canter’s (1977) three spheres of consciousness to define how humans understand a place: physical attributes, activities, and sense. I’m using these categories to collect data for the spaces I am studying in Belo Horizonte.

Secondly, the authors discuss the process of “dencrypting” language to build a more open city. According to

the “Encryption of Power Theory” by Sanín-Restrepo (2016), language is used as a colonial tool to maintain power.

The authors applied this theoretical foundation to an online tool (link) that is mapping resident experiences in place and subvert the conventional language games about “place” that dominate urban planning in Belo Horizonte.

In their own words, “The platform leverages itself as a way for each resident to read their place, far beyond the categories-concepts and indicators-indices built by others. Therefore, it constitutes a proposal for the decryption of the city through the insertion of another language game in the political arena. It is necessary to show that our proposal does not aim to portray the territory, but to demonstrate the complexity of urban dynamics, commonly encrypted.”